National Patient Survey 2024

Survey of UK fertility patients: 2 September - 9 October 2024

Published: March 2025

Download the underlying dataset as .xlsx

Table of contents

- Main points

- Introduction

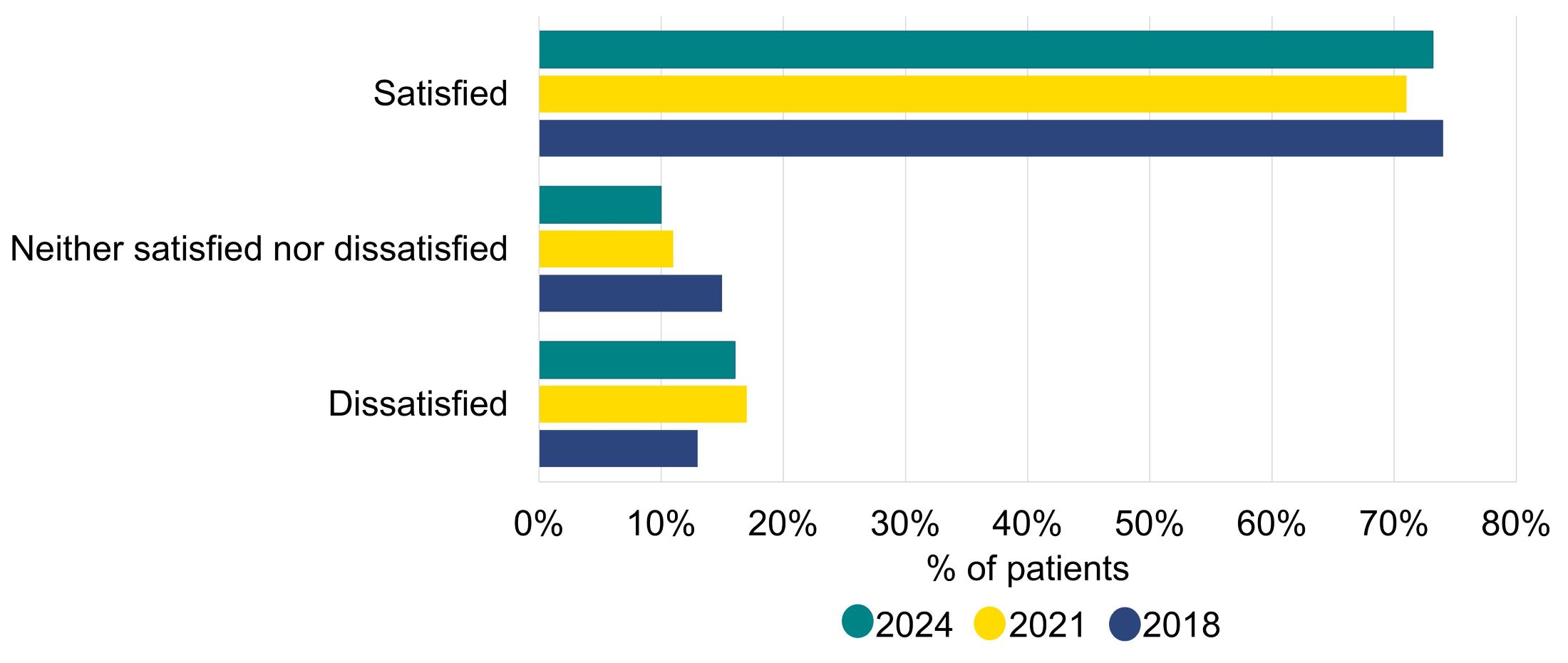

- Section 1: Over 70% of patients were satisfied with treatment

- Section 2: Almost 80% of patients spoke to a GP before treatment

- Section 3: 73% had used an additional test, treatment or emerging technology

- Section 4: Around a quarter of respondents had used donor eggs, sperm, or embryos

- Section 5: 40% of those able to donate would be willing to donate to research

- Section 6: Familiarity with the HFEA increased to 68%

- Qualitative summary

- About our data

Main points

- Fertility patients’ satisfaction with most recent treatment has remained consistent across years at 73%.

- Patient satisfaction with most recent treatment was lower among Asian (50%) and Black (59%) patients, as well as patients above the age of 40 (67%).

- Most patients found information received on what they were consenting to was clear, but many said they received insufficient information on costs, particularly when receiving an itemised bill.

- Only 62% of private patients had received a personalised cost breakdown for their treatment - 40% of whom paid more than what was originally presented to them.

- Location of clinic remains the most important factor for patients when choosing a clinic (62%), followed by success rates (51%).

- Almost 80% of patients spoke to a GP before starting treatment, however, only 43% of these patients were satisfied with their experience of speaking to a GP.

- Patients most commonly began treatment between 7 and 12 months after speaking to a GP (30%). However, 16% of patients waited over two years. Most reported delays in starting treatment due to awaiting referrals, appointments and tests or needing further tests or surgery.

- Almost three quarters of patients used an additional test, treatment or emerging technology during treatment, most commonly medications or supplements (39%).

- Use of the add-on endometrial scratching decreased from 24% in 2018 to 10% in 2024, while use of pre-implantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) increased from 7% in 2021 to 13% in 2024, mainly in those over 38 years of age.

- Half of patients said that their clinic explained the effectiveness of tests, treatments, or technology at increasing the chance of having a baby, but only 37% said their clinic explained risks.

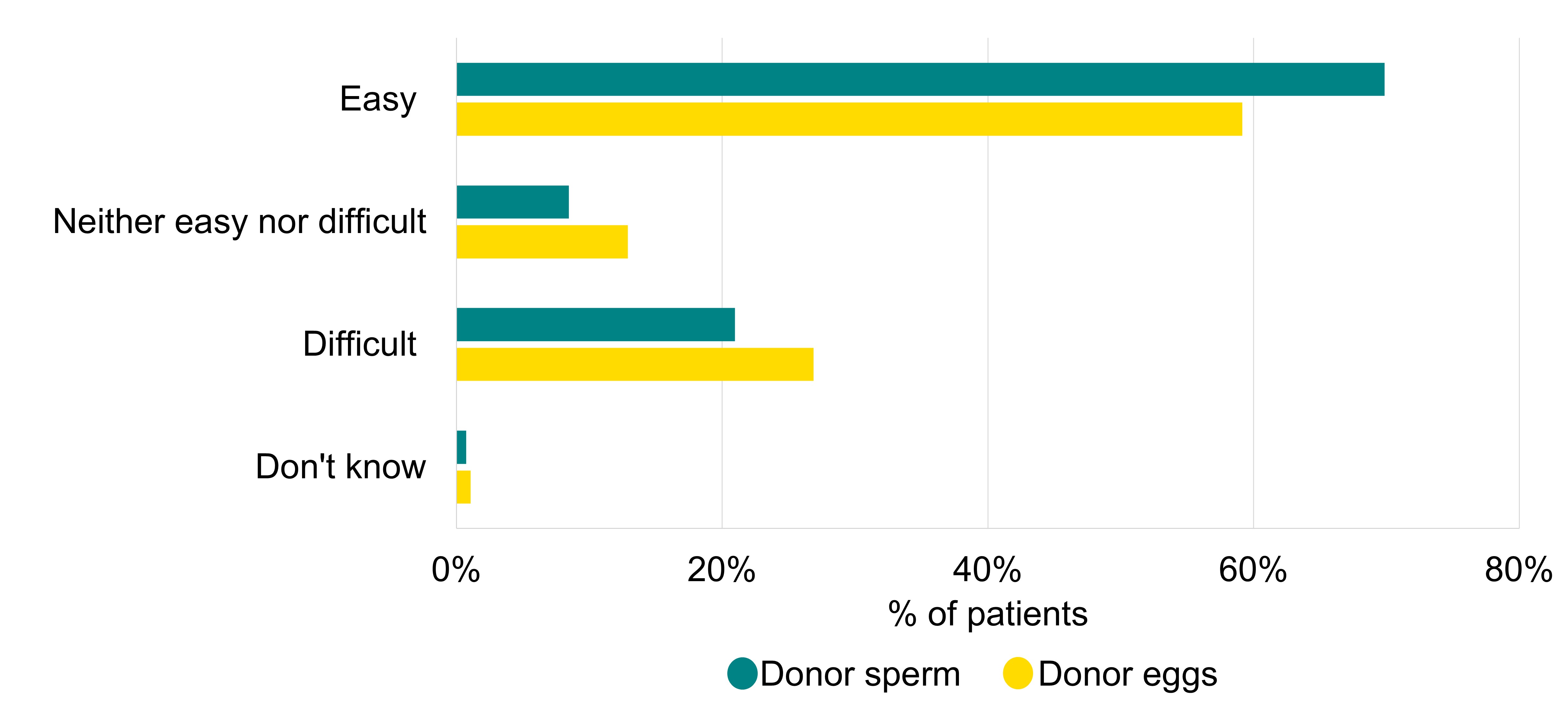

- Around a quarter of respondents had used donor eggs, sperm, or embryos in treatment. 70% of patients who had used donor sperm found them easy to access compared to 59% of patients who used donor eggs.

- Around half of patients using donor sperm used overseas donors, mainly due to increased choice and more information available, with 34% of those patients reporting a lack of clarity on family limits for overseas donors.

- Nearly 70% were familiar with the HFEA, with 58% using the HFEA website for information/support with fertility treatment.

Introduction

The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) periodically surveys fertility patients in the United Kingdom (UK) to better understand their views and experiences. This is the third time the HFEA has carried out a national patient survey. While we have kept many of the questions the same to look at trends over time, we have also made some additions and revisions.

The survey explores the patient pathway, from accessing GP services, choosing a clinic, through to patients’ most recent experience of treatment, egg/sperm donation and additional tests, treatments and emerging technologies.

The number of patients included in this report was 1,500. The profile of respondents is broadly similar to the population of fertility patients taken from our national register. More information on this can be found in the Quality and methodology report.

Most patients were satisfied with the treatment they received at HFEA-licenced clinics. However, some areas for improvement were identified from responses to specific and open-text questions. These are summarised in the report below.

We are grateful to everyone who completed the survey. It has not been possible to cover everything in this summary report, however, we will ensure that responses to this survey continue to be used to inform our work.

1. Over 70% of patients were satisfied with treatment

1.1. Overall satisfaction with treatment

As in previous surveys, most patientsi were satisfied with their latest fertility treatment (Figure 1).

Satisfaction was higher for those who either had a baby, were currently pregnantii (both 88%) or undergoing treatment (69%), compared to those who did not have a baby (50%). Patients were more likely to have taken part in this survey if they had a baby or were currently pregnant (55% vs 24% did not have a baby and 12% no outcome yet). Although it is notable that free text responses showed some still viewed their experience positively even when they had not had their desired outcome. There was little difference to satisfaction rates when comparing privately funded and NHS-funded treatment (73% vs 75%).

Black and Asian patients were less likely to report being satisfied with their treatment (59%*iii and 50% respectively) as were patients over 40 years of age (67%). This may relate to lower birth rates, or a lower proportion of NHS-funded cycles among these patient groups1, 2.

Patients in the North East of England continued to report the highest satisfaction rates (86%* compared to 88% in 20213). The lowest levels of satisfaction were reported by patients receiving treatment in Wales (68%*).

Figure 1. 73% were satisfied with their most recent treatment

Overall satisfaction with recent treatment, 2018-2024

Q: ‘Overall, how satisfied or dissatisfied were you with your most recent experience of fertility treatment?’ Don’t know/Not applicable (n=11) not shown and can be found in the underlying dataset of this report. Blank responses (n=5) excluded (N=1,495).

Download the underlying data for Figure 1 as Excel Worksheet

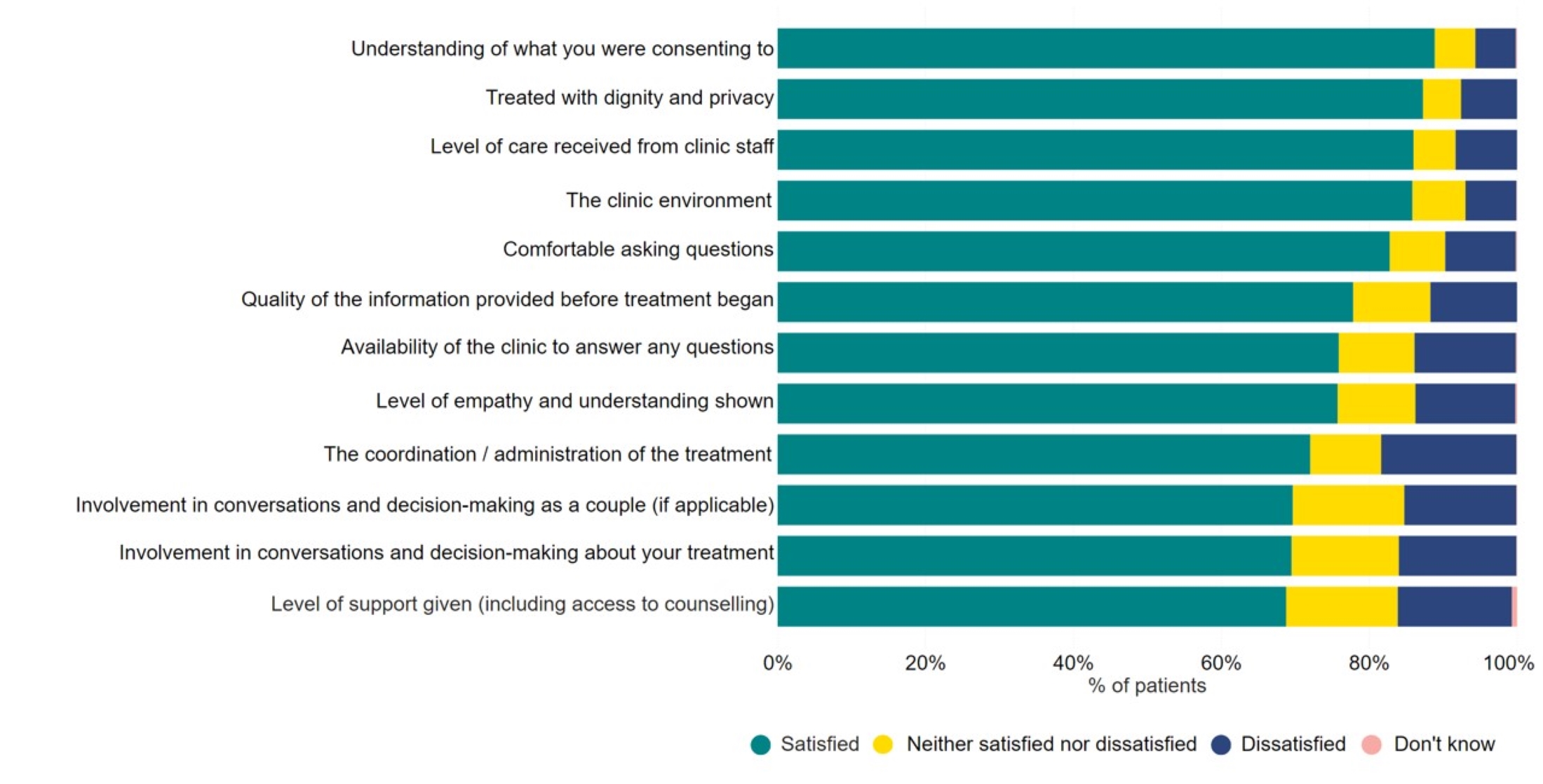

1.2. Satisfaction with various aspects of treatment

Levels of satisfaction were above 65% for all aspects of treatment (Figure 2). Highest satisfaction was with the extent to which patients understood what they were consenting to (89%) and whether they were treated with dignity and privacy (87%).

The lowest proportion of patients reported satisfaction with the level of support given, including access to counselling (69%)iv. Single patients were most likely to be satisfied with the level of support given (75%), as well as the level of empathy and understanding shown to their personal situation (79%), increasing since 2021 (72%). This could be in part due to clinics requiring counselling for those using donor eggs, sperm or embryos.

While satisfaction with most aspects of treatment was high, rates of dissatisfaction were highest with coordination/administration of treatment (18%). Patients in female same-sex and gender diverse couples were more likely to be dissatisfied with the coordination/administration of their treatment compared to opposite-sex couples and single people (24% vs 18 and 17% respectively). Little difference was seen in satisfaction by funding type (71% privately vs 75% NHS-funded).

Both Asian and Black patients were less likely to report satisfaction with the quality of information received (both 66% vs 78% overall) and the extent to which the clinic was available to answer questions (66% and 57% respectively, vs 76% overall).

Figure 2. Satisfaction was highest with understanding what patients were consenting to, and lowest for level of support

Satisfaction with various aspects of treatment, 2024

Q: ‘How satisfied or dissatisfied were you with…?’ Not applicable responses were excluded with the number dependent on option, view the underlying dataset for more information (N=1,497).

Download the underlying data for Figure 2 as Excel Worksheet

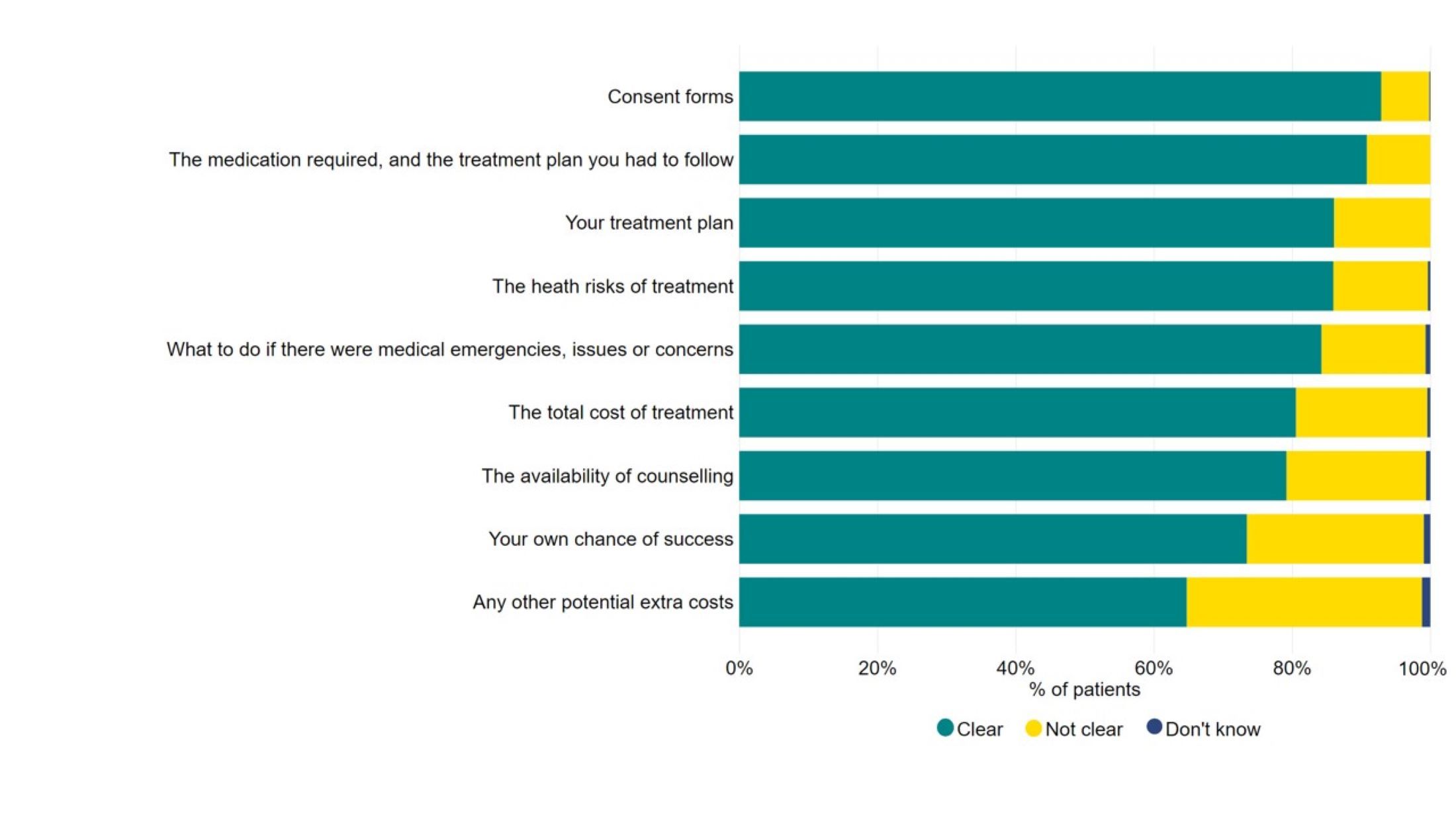

1.3. Communication of specific aspects of treatment

The HFEA Code of Practice has a number of requirements for information that patients must be given before starting treatment. Overall, patients found communication of most aspects of treatment clear (Figure 3).

Most patients (73%) felt their own chance of success was communicated clearly, an improvement from 68% in 20213. However, this varied by funding, age and ethnicity. Privately funded patients reported higher clarity (81% vs 66% NHS-funded), as well as patients aged 43 and over (88% vs 71% aged 18-34). Black and White patients were more likely to report that their chance of success had been explained clearly compared to Asian and Mixed patients (77% and 74% vs 65% and 61% respectively).

Figure 3. Patients had the most clarity on consent forms, medication required, and the treatment plan they had to follow

Clarity of communication of aspects of treatment by clinics, 2024

Q: ‘To what extent, if at all, were each of the following aspects clearly communicated to you by the clinic before treatment was agreed?’ Not applicable responses excluded with the number dependent on option, view the underlying dataset for more information (N=1,498).

Download the underlying data for Figure 3 as Excel Worksheet

Of the patients who underwent privately funded treatment, 62% reported that they were given the required personalised cost breakdown/itemised bill at the beginning of their treatment.

Almost 60% of private patients paid what was on their original bill, but 40% paid more. Almost half (48%) of patients aged 43 or over reported paying more than their original bill, mainly due to medication or cycle changes. Patients aged 43 or over were also more likely to have used an additional test, treatment or technology in their treatment, which may contribute to overall costs (see Section 3).

1.4. Comments on experience of most recent treatment

Patients provided further commentary on recent experience at their clinic through free text. Key factors that played a role in how patients viewed their treatment were identified and are outlined in the qualitative summary at the end of this report.

Figure 4. Multiple factors played a role in patient experience of their most recent treatment

Factors which affected patient experience during their most recent treatment cycle

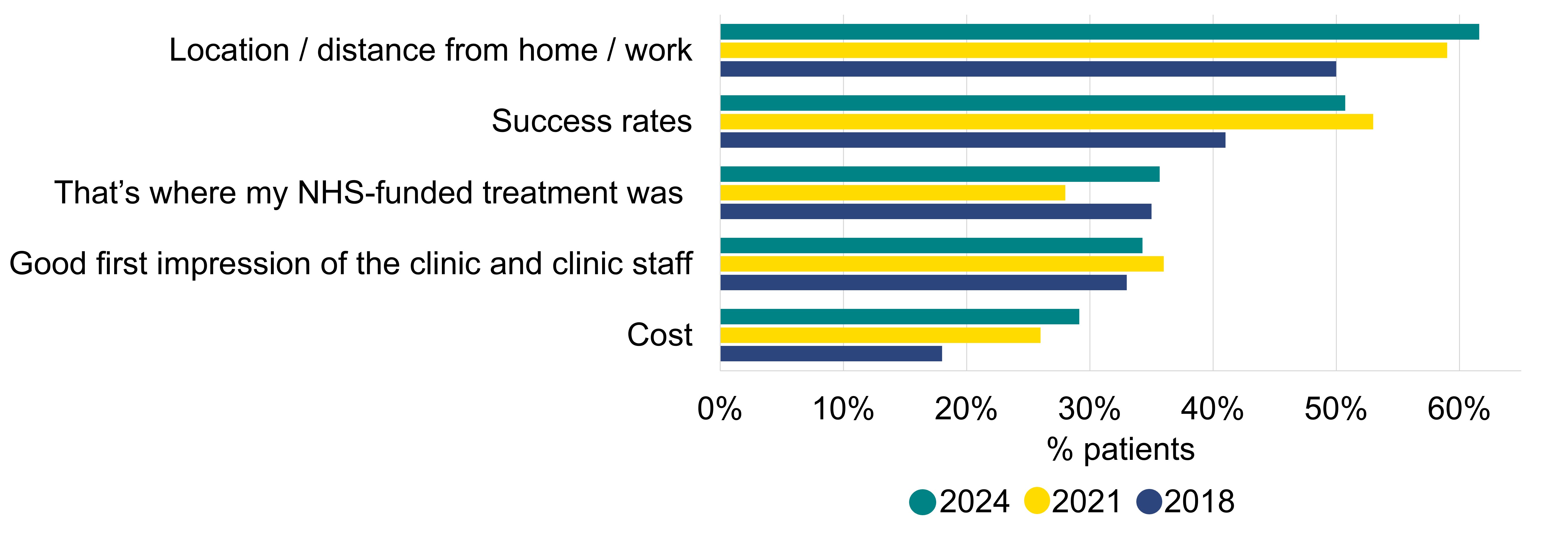

1.5. Important factors when choosing a clinic

Location remains the most important factor for patients when choosing a clinic (62%), increasing from 50% in 2018 (Figure 5).

Cost was recorded as more important for Black patients (47%* vs 29% all other patient groups combined) and single patients (50% vs 25% opposite sex-couples). This may relate to the lower levels of NHS funding among these patient groups1, 4.

Choosing a clinic that specialises in supporting LGBTQIA+ patients was the second most important factor for patients in female same-sex and gender diverse couples (52%).

Figure 5. Location remains the most important factor when choosing a clinic

Most important factors when choosing a clinic, 2018-2024

Q: ‘Which of the following factors, if any, were most important to you when choosing a fertility clinic?’ Only top five options have been shown for each patient group (N=1,500).

Download the underlying data for Figure 5 as Excel Worksheet

2. Almost 80% of patients spoke to a GP before treatment

2.1. Speaking to a GP

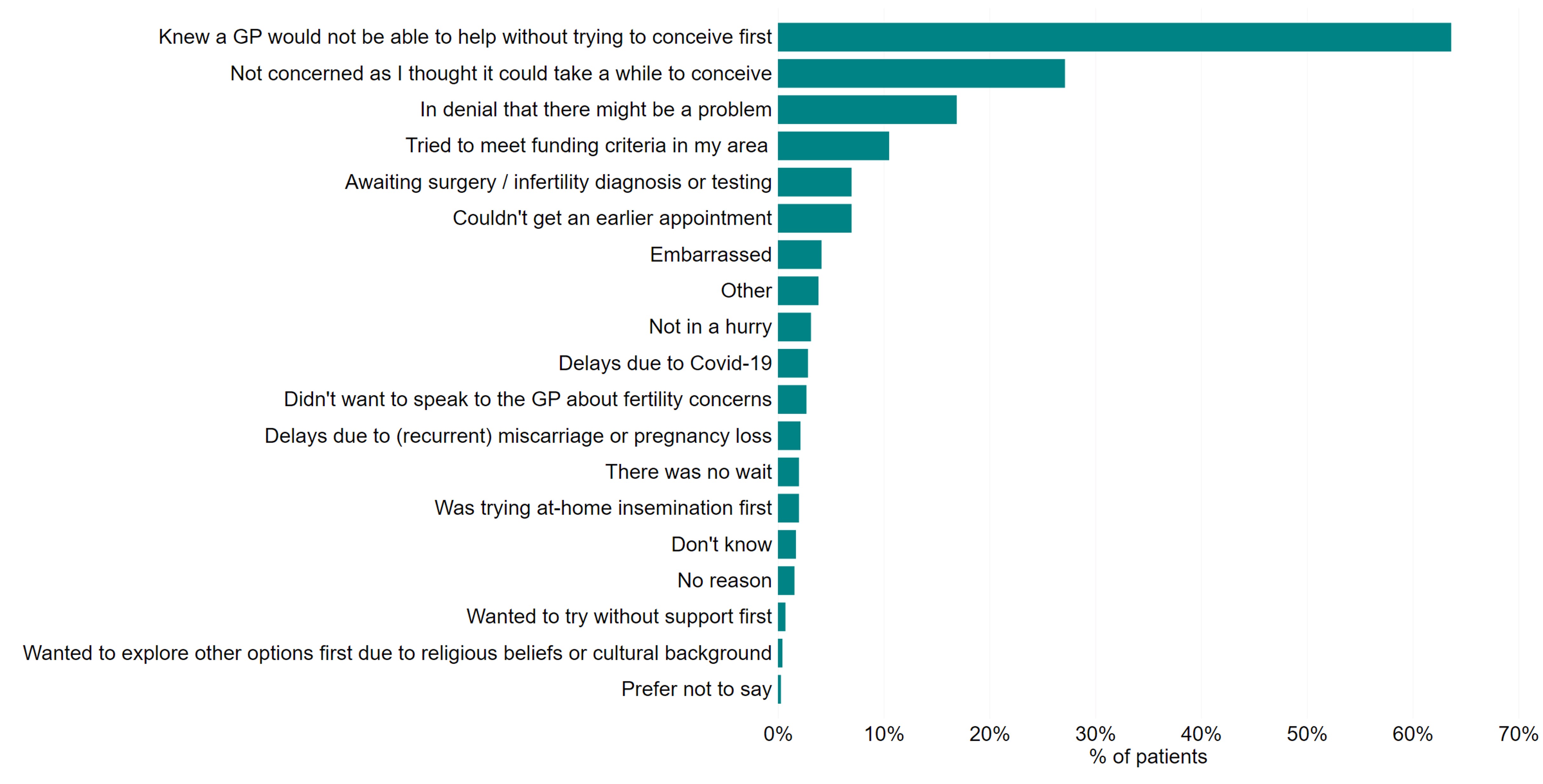

Almost 80% of patients spoke to a GP before treatment, with most doing so within two years of starting to try to conceive (80%), similar to 20213. The most common reason patients waited over a year to speak to a GP was that they knew a GP would not be able to help before trying to conceive first (Figure 6).

Patients in female same-sex, gender diverse couples, and single patients were less likely to visit a GP prior to starting treatment (48-45% did visit a GP) compared to opposite-sex couples (85%). Similarly, older patients were less likely to visit a GP prior to starting treatment (80% aged 18-34 vs 66% aged 43 or over).

Figure 6. Over half knew a GP would not be able to help without trying to conceive first

Reasons for wait to speak to a GP about concerns, 2024

Q: ‘Which of the following reasons, if any, explain the wait to speak to a GP to discuss treatment?’ Those who did not speak to GP (n=345), who spoke to a GP before a year of trying (n=362), or who did not provide details on the length of time before speaking to a GP were excluded (n=1). Those who spoke to a GP before trying to conceive were not asked this question (N=704).

Download the underlying data for Figure 6 as Excel Worksheet

2.2. Starting treatment

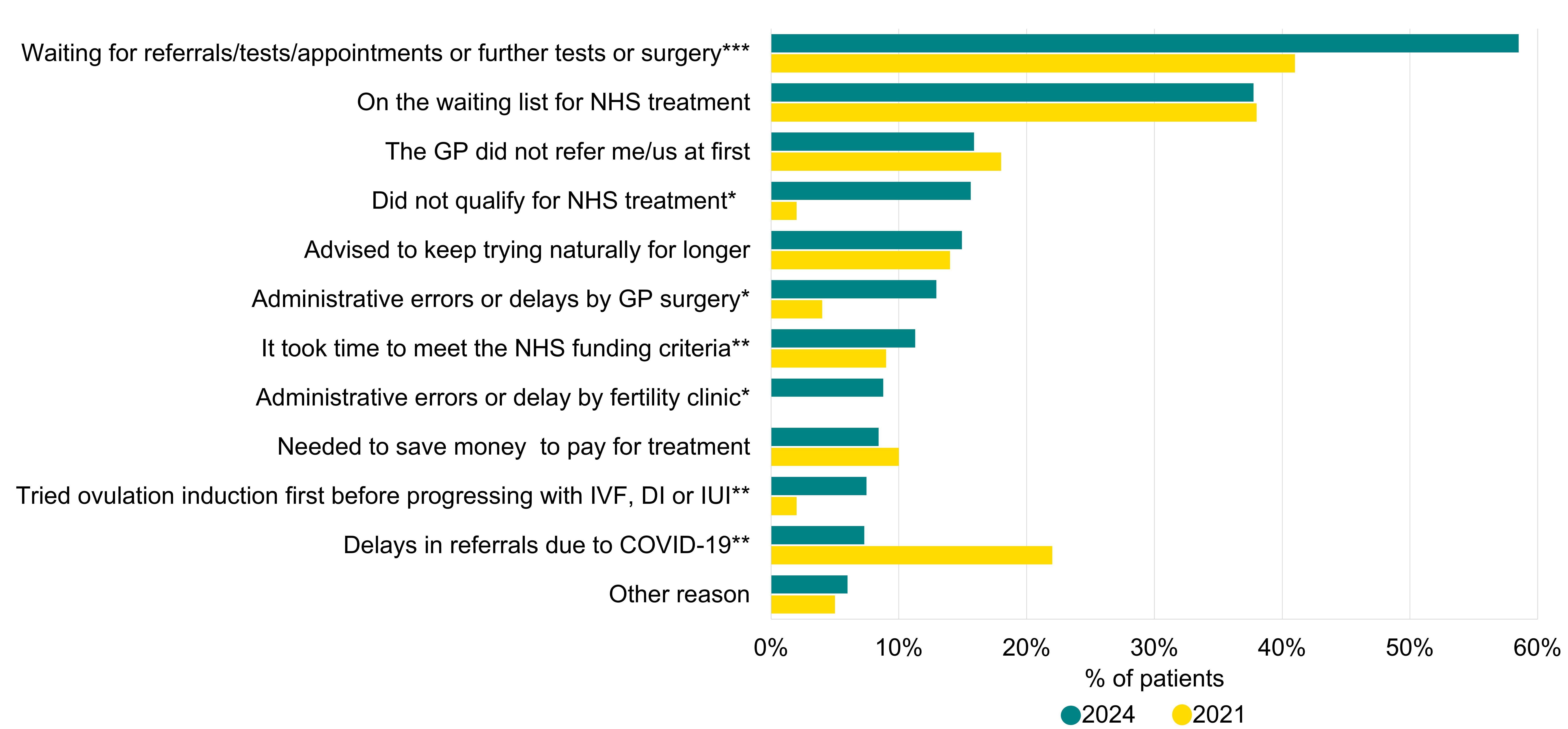

Patients most commonly began treatment between 7 and 12 months after speaking to a GP (30%). However, 16% waited more than two years. Half (53%) of those having treatment privately started treatment within a year, while only 35% of NHS-funded patients had started treatment during that same period.

Almost 60% reported waiting for referrals, appointments and/or tests or needing further tests or surgery as a reason for a delay in starting treatment (Figure 7). These delays were likely to have occurred prior to a patient entering a clinic.

A higher proportion of NHS patients reported this than private patients (69% vs 49%, respectively). This could be a knock-on effect of the current wait times for gynaecology services, where over three quarters of a million people are waiting months to years5.

Figure 7. Most delays were due to waiting for referrals, appointments and tests

Reasons for delay in starting treatment, 2021 and 2024

Q: ‘Could you tell us the reason(s) for any delay in starting treatment after speaking to your GP?’ Only top answers are shown in this diagram. Those who did not speak to a GP were not asked this question (N=1,152). *represents a new option added in 2024, **represents an option that has changed since previous surveys, *** represents a category which has been combined with another, similar category to support interpretation

Download the underlying data for Figure 7 as Excel Worksheet

Less than half (43%) of patients who spoke to a GP about their options were satisfied with their experience, a further decrease from previous surveys3, 6.

Patients who had either had a baby or were currently pregnant were more likely to be satisfied with speaking to a GP (46% vs 38 % who did not have a baby). Similarly, patients who started treatment within six months were more commonly satisfied (46% vs 35% over 18 months). Privately funded patients were less likely to be satisfied than NHS patients (29% vs 57%, respectively).

3. 73% had used an additional test, treatment or emerging technology in treatment

3.1. Use of additional tests, treatments or emerging technologies

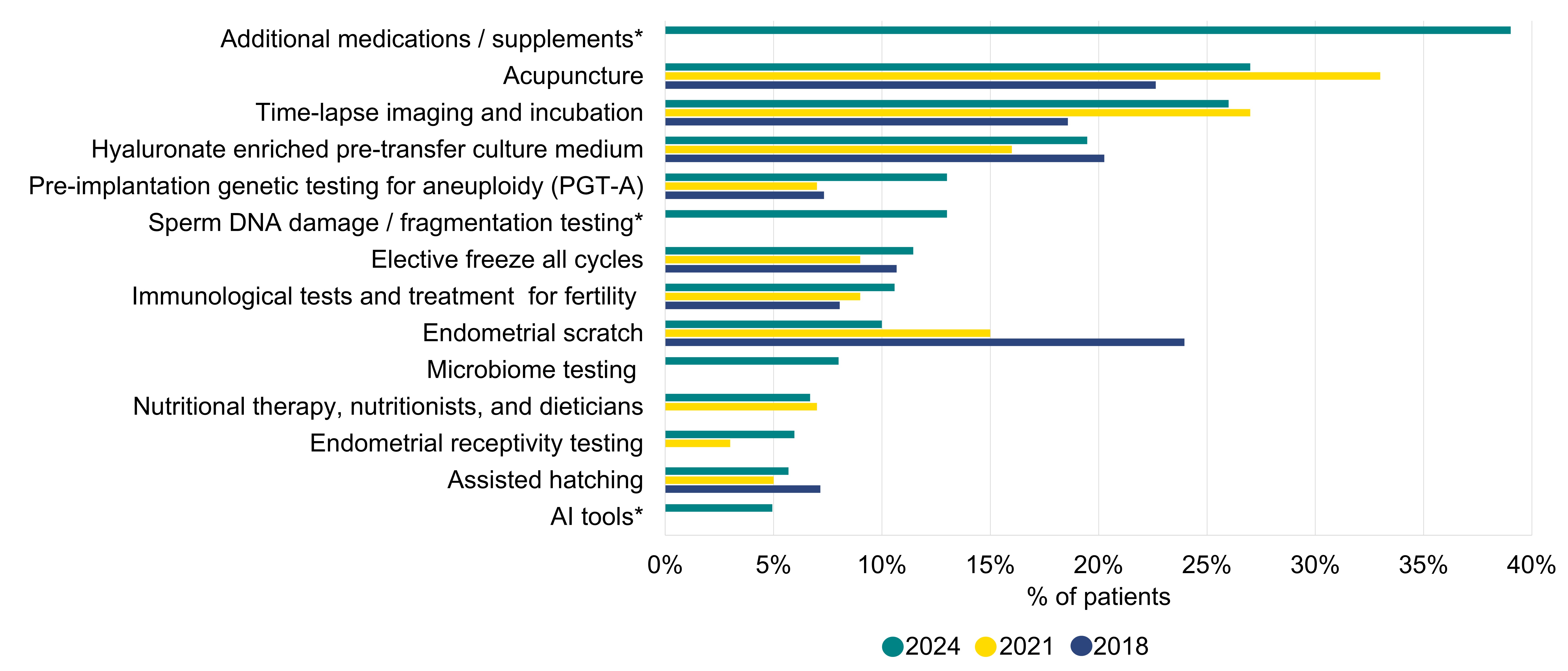

Since 2017, the HFEA has worked to reduce the use of add-ons in treatment, since almost all remain unproven at increasing the chance of having a baby for most patients7, 8. These questions covered the use of treatment add-ons, as well as other additional tests and emerging technologies.

Three-quarters (73%) used an additional test, treatment or emerging technology (Figure 8). Additional medications/supplements (39%) were most commonly used followed by acupuncture (27%) and time-lapse imaging (26%v).

Black patients were most likely to have used acupuncture (44%), additional medications or supplements (64%) or elective freeze all cycles (28%) compared to patients of any other ethnic group.

Patients who underwent one cycle were less likely to have used an additional test, treatments or emerging technology (62% vs 86% of those who had five or more cycles). NHS-funded patients were also less likely to have used these in treatment (57% vs 76% of private patients). Patients in Scotland (62%) and North East of England (64%) had the lowest use of additional tests, treatments or technologies, which may relate to the high proportion of NHS-funded cycles in these regions2.

This survey has shown changes in the use of two add-ons over the years. Endometrial scratching, an amber rated add-on for increasing the chances of having a baby for most fertility patients, decreased from 24% in 20186 to 10% in 2024. The use of Pre-implantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) nearly doubled from 7% in 2021 to 13% in 2024.

Patients aged 40–42 were most likely to have used PGT-A (28%) compared to patients of any other age group. 56% of those reporting use of PGT-A had treatment in London, this is also the region which had the highest proportion of respondents aged 40-42 (19%). The HFEA add-ons rating has PGT-A graded as grey among older women, because there is insufficient moderate/high quality evidence for PGT-A reducing the chances of miscarriage or improving chances of having a baby.

Figure 8. Endometrial scratching and PGT-A use has changed over time

Use of additional tests, treatments or emerging technologies, 2018-2024

Q: ‘In relation to your most recent fertility treatment, were any of the following additional tests, treatments (often known as treatment add-ons) or emerging technologies used?’ Only the top options reported are shown in this figure. Patients who answered ‘None of the above’ (N=407) or ‘Not sure’ (N=75) were not included in this figure. Please see the underlying dataset for full list of additional tests, treatments, and technologies (N=1,500). *represents a new option added in 2024.

Download the underlying data for Figure 8 as Excel Worksheet

3.2. Discussion prior to, and reasons why an additional test/treatment/technology was used

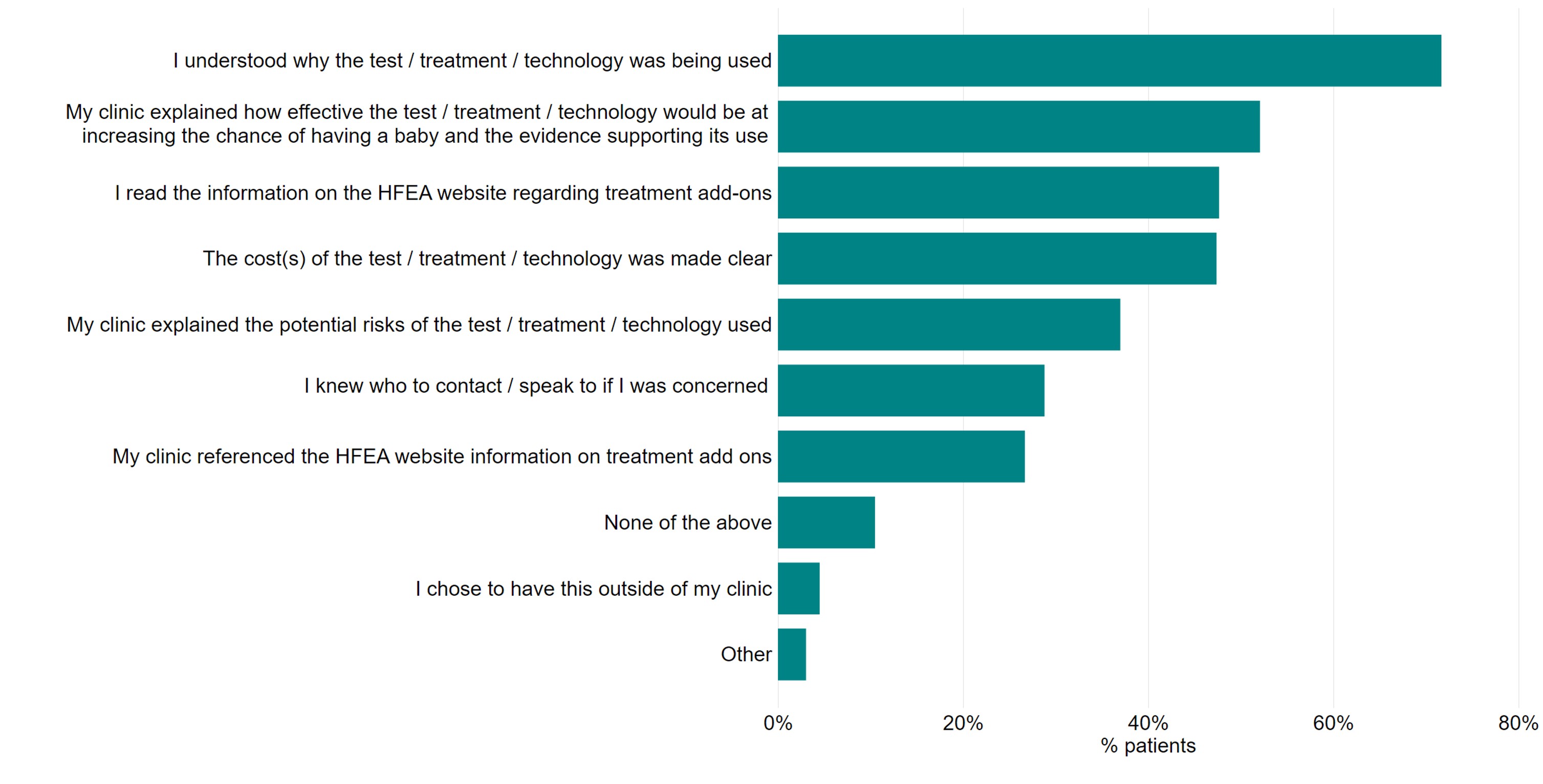

The HFEA Code of Practice provides guidance to clinics to ensure that patients using additional tests, treatments or emerging technologies have sufficient information on risks and the impact on increasing the chance of a baby9.

28% of patients using additional tests, treatments or technologies did not report understanding why it was used. Additionally, over half (52%) of patients said that their clinic explained how effective they were at increasing the chance of having a baby and evidence of supporting its use (Figure 9). Around half of patients had read information available on the HFEA website (48%), however only 27% reported that their clinic referenced HFEA information on treatment add-ons.

Only 37% of patients said that any potential risks of the tests, treatments or technologies used were explained to them, similar to 20213. This was less likely for patients aged 43 or older (22%) than patients 35-37 (41%).

Many (59%) chose to have an additional test, treatment or technology based on clinic recommendation. This was either based on the clinic stating the treatment would increase the chance of having a baby (44%) or for another reason (14%). Privately funded patients more commonly used these on clinic advice (61%) compared to NHS-funded patients (39%). However, almost a third (30%) requested to have an additional test, treatment or technology themselves.

Figure 9. Almost 30% didn’t understand why an additional test, treatment, technology was used

Discussion prior to having an additional test/treatment/technology, 2024

Q: ‘Before having any of these additional tests, treatments or technologies, which of the following applied?’ Patients who answered ‘None of the above’ (n=407) to additional tests, treatments, technologies were excluded (N=1,087).

Download the underlying data for Figure 9 as Excel Worksheet

4. Around a quarter of respondents had used donor eggs, sperm, or embryos

4.1. Accessing donor eggs, sperm, or embryos

Around a quarter of respondents had used donor eggs, sperm or embryos (27%), with donor sperm being most common.

When asked how easy it had been to access donor gametes, 70% of those using donor sperm felt access had been easy, compared to only 59%* of those using donor eggs (Figure 10vi).

Asian, Black, Mixed and Other patients were slightly less likely to report finding either eggs or sperm easy to access (58%* vs 68% of White patients). This likely relates to our previous findings that Asian, Black, Mixed and Other ethnicity patients had more difficulty accessing donor gametes meeting their criteria3.

Figure 10. Most patients found donor eggs and sperm easy to access

Ease of accessing donor eggs and sperm, 2024

Q: ‘How easy or difficult did you find it to access donor eggs and donor sperm?’ (N=365).

Download the underlying data for Figure 10 as Excel Worksheet

Most patients using donor eggs were treated using eggs donated in the UK arranged through a UK clinic or donor bank (69%). Those using donor sperm were slightly more likely to be treated using donor sperm imported from overseas (51% vs 44% UK donor sperm).

Those in female same-sex and gender diverse couples (71%), and single patients (74%) were more likely to find donor sperm easy to access compared to opposite-sex couples (54%*). These patient groups were also more likely to use imported sperm than opposite-sex couples (49% and 58% vs 37%*, respectively).

The most common reasons why a patient used imported donor sperm were increased choice of donors (69%) and more information about the donor (56%vii).

4.2. Communication of aspects of donor treatment

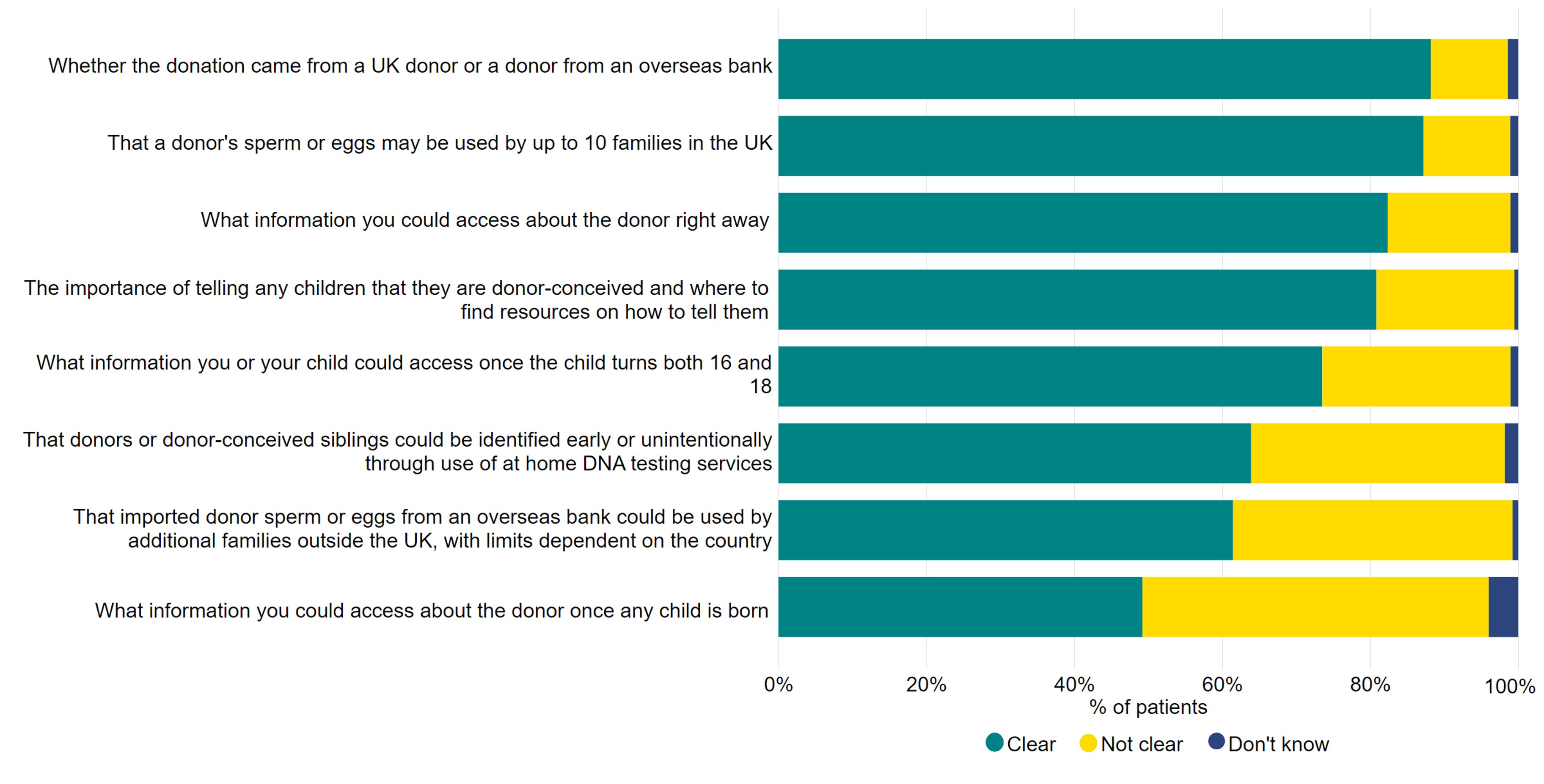

Differences can be seen in communication of the information available about a donor and donor family limits with patients (Figure 11).

Most patients found communication about the information available to them right away (82%) and once the child turns 16 and 18 (74%) clear but found communication on what information was available once a child was born less clear (49%).

Most patients also found communication on donor family limits in the UK clear (87%). However, 34% of those who used donor eggs, sperm or embryos from overseas reported that communication on the potential use of imported donor eggs or sperm by additional families outside the UK, with limits dependent on the country, was unclear.

The HFEA Code of Practice advises what information patients are able to access about donors and that the clinic should explain the 10 family limit only applies to treatment in the UK9.

Figure 11. Communication of the information available about donors at birth and donor family limits outside of the UK was unclear

Communication of aspects of donor treatment, 2024

Q: ‘To what extent were each of the following aspects of egg, sperm or embryo donation clearly communicated to you by the clinic?’ Not applicable responses were excluded from this figure with the number dependent on option, view the underlying dataset for more information (N=392).

Download the underlying data for Figure 11 as Excel Worksheet

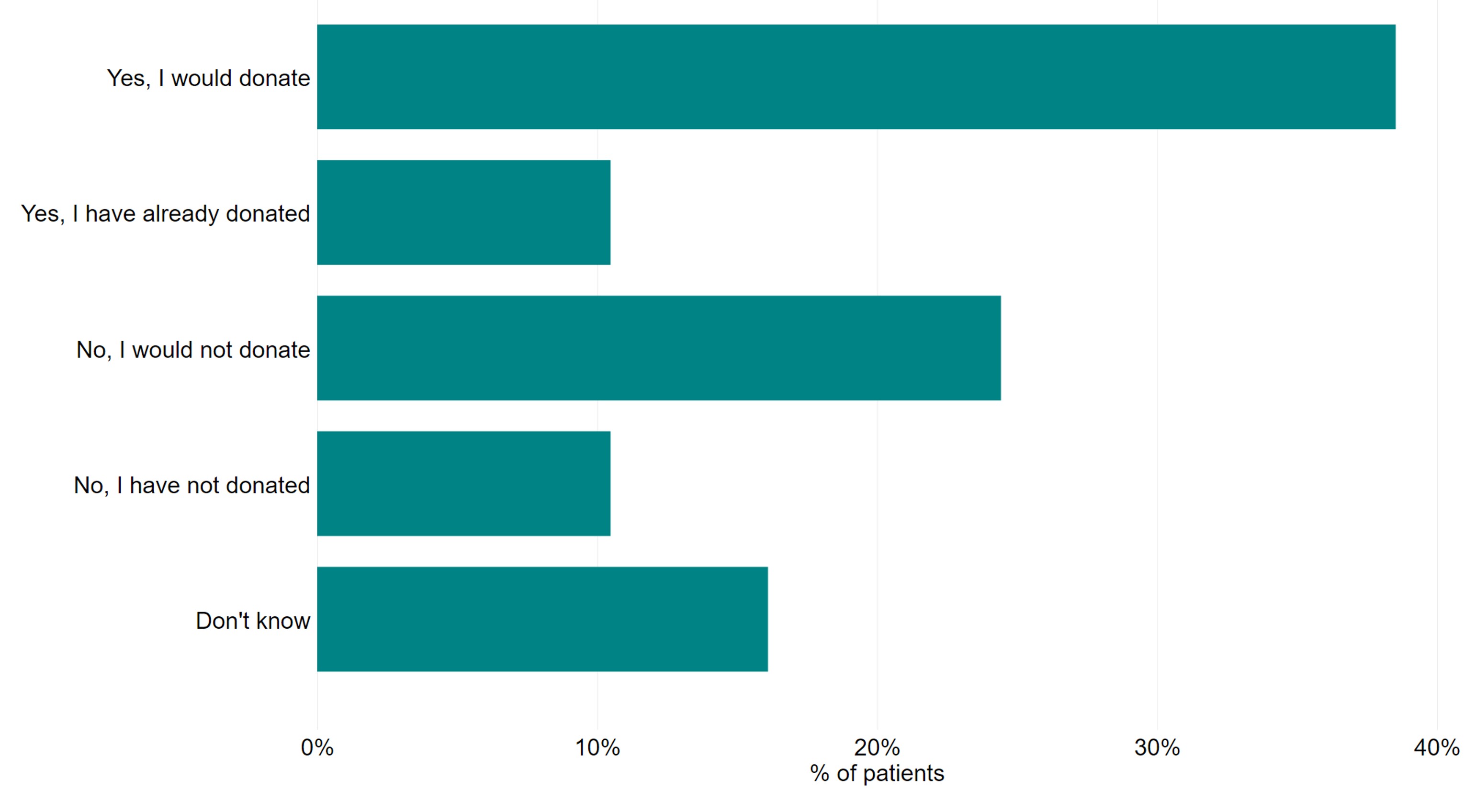

5. Almost 40% of those able to donate would be willing to donate to research

Patients were asked whether they had, or would be willing to, donate eggs, sperm or embryos to researchviii. While only 10% reported that they had donated their eggs, sperm or embryos already, 39% of patients would consider donating in the future (Figure 12).

Willingness to donate to research was highest among patients aged 18-37 (40%) and patients currently in treatment (50%). Similarly, single patients were most likely to report that they would donate to research (50%), followed by female same-sex and gender diverse couples (41%), then opposite-sex couples (37%).

Similar proportions of White (39%), Mixed (38%*) and Black (37%*) patients reported that they would donate eggs, sperm, or embryos to research, whereas Asian patients were slightly less likely to report this (31%*). Lower proportions of Asian patients willing to donate has been seen in other work and may relate to cultural and religious factors around donation10, 11.

Figure 12. 39% would be willing to donate their eggs, sperm, or embryos to research

Donation of eggs, sperm, or embryos to research, 2024

Q: ‘Would you donate, or have you donated, your eggs, sperm, or embryos to research?’ Patients who answered ‘Not applicable/I am unable to donate’ (n=199) or who did not answer the question (n=3) were excluded (N=1298).

Download the underlying data for Figure 12 as Excel Worksheet

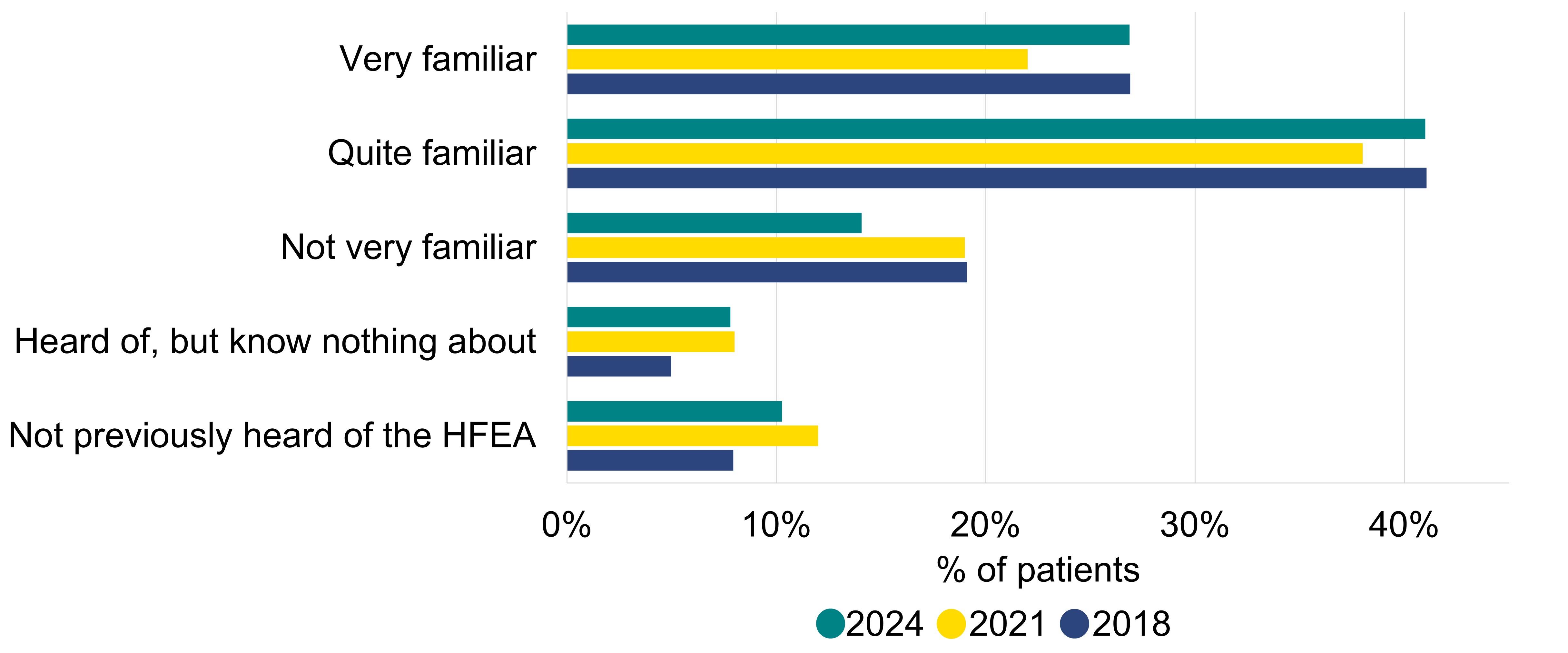

6. Familiarity with the HFEA increased to 68%

6.1. Familiarity with the HFEA

Patients were asked whether they knew about the HFEA and the information we provide. Familiarity with the HFEA has increased since 2021 from 60% to 68%.

Both Asian and White patients were less likely to be familiar with the HFEA (63%* and 67%, respectively) compared to patients from Black (83%*) or Mixed (83%*) ethnic backgrounds. This is reflected in the lower number of respondents from Asian patients in the study overall compared to the fertility populationix. Similar levels of familiarity were seen between private and NHS-funded patients (66% vs 60%).

Figure 13. Familiarity with the HFEA returns to 2018 levels

Familiarity with the HFEA, 2018-2024

Q: ‘Before this survey, how familiar were you with the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA)?’ (N=1,500).

Download the underlying data for Figure 13 as Excel Worksheet

6.2. Information/support sources

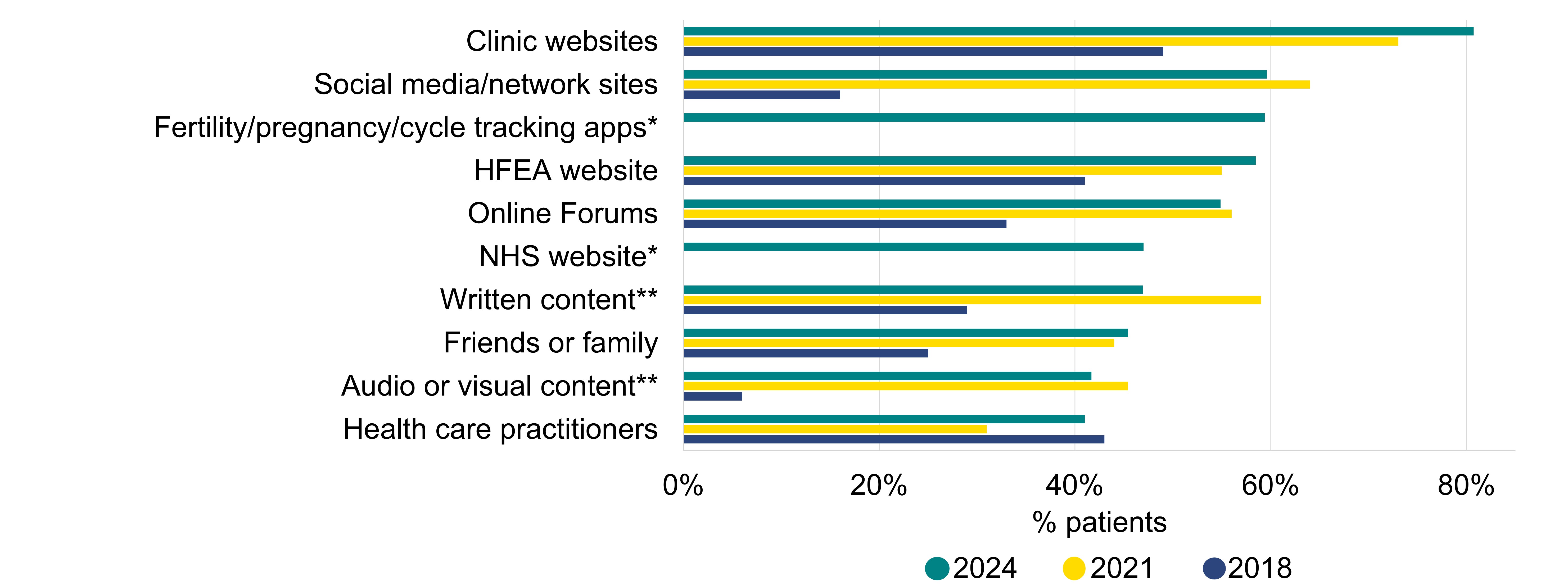

The most commonly used information and support sources on fertility were clinic websites (81%), social media/networking sites (60%) and fertility/pregnancy tracking apps (59%) (Figure 14). Use of clinic websites nearly doubled since the 2018 survey (49% to 81%).

Figure 14. Clinic websites remain the most common source for information about treatment

Information/support sources used by patients, 2018-2024

Q: ‘Which, if any, of the following have you used to find information about fertility treatment?’ Only the top options reported are shown in this figure. Please see the underlying dataset for full list (N=1,500).*represents a new option added in 2024, **represents an option that has changed since previous surveys.

Download the underlying data for Figure 14 as Excel Worksheet

Qualitative summary

Overall quantitative findings showed that most patients were satisfied with their treatment. However, in addition to noting areas of good practice, many responses highlighted areas where some improvements could be made. These responses have been grouped into ten key factors that effected experience of fertility treatment (Figure 4).

Coordination/administration of treatment

Many patients described situations where administration of their treatment did not meet their expectations. This ranged from appointments being incorrectly scheduled, receiving incorrect or unclear information about their treatment or billing to mistakes or errors made by clinic staff. In some cases, these errors resulted in delays in accessing services or cycles being cancelled. Patients valued being able to see the same clinician or having a “named nurse” throughout their journey.

Involvement in the decision-making process

Having the opportunity to be involved in the decision-making process was an important factor for some. Where patients were able to be involved in the decision-making process, this was often described positively. Notably, in cases where patients had undergone multiple cycles, they described feeling more comfortable asking questions, and able to self-advocate “and say what [they] want and why”.

Involvement of their partner in treatment

In some cases, patients commented on how their partner was involved in their treatment. Comments commonly referred to feeling as though there was insufficient investigations into their partner’s fertility and inconsistencies with how they were “treated as an equal” or included in aspects of treatment. Patients highlighted the knock-on effect this had, feeling as though it was “all on” them/their “fault” for having to go through treatment.

How well their clinic communicated with them

The ability to contact their clinic, and how information was shared was important to many patients. These patients described difficulty in directly contacting staff, instead going to general inboxes or central switchboards. Where negative outcomes, such as a failed transfer, or pregnancy loss, occurred, timely and “empathetic” responses were viewed positively. Patients valued the opportunity to provide feedback or discuss any questions they may have with clinic staff.

A lack of, inconsistent, or “generic” information on success rates, add-ons, donor family limits or the cost of treatment was raised. This lack of information was often viewed as a lack of transparency and led to patients experiencing uncertainty, frustration or distress.

Whether they felt supported or they were treated with empathy/care

Being treated with empathy, sensitivity and care was particularly relevant in cases where patients experienced negative outcomes, or unexpected changes to their treatment. Some patients felt that infertility was treated as “routine” by staff, when patients associate it with “shame” and “anxiety”. Where patients felt they were treated with empathy or supported, they were more likely to convey a positive experience. Some patients attributed a lack of empathy or support specifically to their personal circumstances, particularly same-sex female couples, single, older, or Black patients. This led to patients feeling “disregarded” by their clinic.

Experiencing delays, either prior to accessing or during treatment

Patients who mentioned delays often commented on wait times for treatment or fertility investigations, experiencing slow, or lost referrals. While not directly related to their treatment, this was viewed as part of the process. A lack of clarity on how long the referral process would take was mentioned, with patients feeling unprepared for the waits they experienced. Once in treatment, patients described waits to have appointments, or to access specific services. Patients who experienced negative outcomes such as pregnancy loss described having to wait to speak to their clinic or to access support, which had a significant emotional impact with one patient feeling as though they were “left ourselves to go through a difficult thing”.

Whether they received high-quality treatment/care

Some commented on the quality of treatment or care they received. Many specifically referred to clinical care, with some highlighting cases where staff went above and beyond. Patients reported mixed experiences with staff, however, patients were more likely to refer to staff positively where they felt staff were supportive, knowledgeable or provided excellent care. Many reflected on their care positively where they felt their treatment was tailored to them or where there was a “personal touch”. In cases where this was missing, the experience was often described as being on a “fertility conveyor belt”.

The impact of cost of treatment (and funding status)

Patients commonly criticised the access criteria and provision of NHS funding, with the allocation of funding based on Body Mass Index (BMI), location, sexuality or relationship status particularly viewed as unfair. Many viewed the cost of treatment as a barrier to access with patients having to “decide if they can afford a baby”. While some felt as though paying more meant a higher quality of care, others found this an additional source of stress or that the process was more about “making money”. Some NHS-funded patients felt that their funding status meant that they were viewed as less important than private patients leaving them feeling “neglected”.

Their ability to access support services (such as counselling)

The ability to access, and the quality of, support services was also important to patients. Many highlighted the impact of experiencing infertility and treatment had on their mental health, describing it as leaving them “struggling mentally/emotionally”, with those who had a negative experience or did not achieve their desired outcome most affected. Most described a desire to speak to someone, though many outlined difficulties in accessing these services.

Whether they were able to find out why they were experiencing issues with conceiving

Finally, many wanted to have a greater understanding of their fertility. This was particularly common from patients experiencing unexplained infertility who often felt that they were perhaps “pushed down the IVF route” or those who did not experience their desired outcome.

About our data

The HFEA ran the National Patient Survey 2024 from 2 September to 9 October 2024. The survey was open to anyone who had undergone fertility treatment in the UK, including patients, partners, intended parents and surrogates. The information obtained is a snapshot of the patient experience of various aspects the fertility sector from 2019 to 2024.

The survey is broadly representative of the fertility patient population, with a few exceptions. More details can be found in the Quality and methodology report. Due to small numbers, we have had to consider responses from patients in transgender, non-binary and gender diverse partnerships and female same-sex couples together to draw comparisons. Additionally, in some cases where base sizes were small, responses from Asian, Black, Mixed and Other patients were also considered together. Limitations of this is further detailed in our Quality and methodology report.

Patients who responded “Not applicable” to a question were excluded from analysis where relevant and corresponding n numbers are included in the figure notes directly below. Total counts are available in the underlying dataset of this report.

Over time, due to the evolving nature of the fertility sector and need for continuous improvement, there have been some changes to the way some of the questions have been presented and/or the answer options provided to patients. In some cases, this has meant that comparison between years is not possible.

The report is based on responses from patients, partners, intended parents and surrogates. However, we use the term ‘patients’ throughout as an umbrella term to include each of these groups.

About the HFEA

The HFEA is the UK’s independent regulator of fertility treatment and research using human embryos. Set up in 1990 by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act, the HFEA is responsible for licensing, monitoring, and inspecting fertility clinics and research centres – and taking enforcement action where necessary – to ensure everyone accessing fertility treatment receives high quality care.

The HFEA is an ‘arm’s length body’ of the Department of Health and Social Care, working independently from Government providing free, clear, and impartial information about fertility treatment, clinics and egg, sperm, and embryo donation.

The HFEA collects and verifies data on all treatments that take place in UK licensed clinics which can support scientific developments and research and service planning and delivery.

The HFEA is funded by licence fees, IVF treatment fees and a grant from UK central government. For more information, visit hfea.gov.uk.

Contact us regarding this publication

Media: press.office@hfea.gov.uk

Statistical: intelligenceteam@hfea.gov.uk

Accessibility: comms@hfea.gov.uk

Footnotes

- Throughout the report, the term ‘patient’ has been used as an umbrella term to include patients, partners, intended parents and surrogates. We have taken the decision to refer to all respondents as patients, since many partners, intended parents and surrogates are also patients, and will also have been involved in treatment themselves.

- This does not include patients who were currently pregnant through natural conception, only those who were pregnant from fertility treatment.

- There are small base sizes for some sub-groups. Where this is the case, we have flagged this with an asterisk (*).

- All clinics are required under the HFE Act 1990 to provide sufficient access to counselling prior to treatment, and guidance from the HFEA stating that centres should provide proper counselling throughout treatment.

- Due to changes in the structure of this question, direct comparisons with previous survey responses have limitations (see Quality and methodology report).

- Due to the small number of responding patients using donor eggs and sperm and donor embryos, these are not included, please see the underlying dataset for more.

- Due to the small numbers of patients who imported donor eggs or donor embryos, we have not reported on these findings here, please see underlying dataset for more.

- Patients would only consent to donate eggs, sperm or embryos that were either unsuitable or not needed for further treatment (for more information see Donating to research).

- See Quality and methodology report for more details of breakdown of total respondents by ethnic background.

Notes on National patient survey 2024

- Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority. Ethnic diversity in fertility treatment 2021 (2023).

- Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority. Fertility treatment 2022: preliminary trends and figures (2024).

- Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority. National Patient Survey 2021 (2022).

- Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority. Family formations in fertility treatment 2022 (2024).

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG). New RCOG report reveals devastating impact of UK gynaecology care crisis on women and NHS staff (2024).

- Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority. Pilot national fertility patient survey (2018).

- Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority. Treatment add-ons with limited evidence.

- Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority. The responsible use of treatment add-ons in fertility services: a consensus statement (2023).

- Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority. HFEA Code of Practice. (2023)

- Purewal S. and van den Akker, O.B.A. British women’s attitudes towards oocyte donation: Ethnic differences and altruism, Patient Education and Counseling. (2006)

- Culley, L., Hudson., N., and Rapport., R. Assisted Conception and South Asian communities in the UK: public perceptions of the use of donor gametes in infertility treatment , Human Fertility, 2013, 16: 48–53

Review date: 26 March 2027